Rotator cuff tears can happen suddenly, from an injury such as a fall, or they may develop slowly due to overuse or the natural aging process.

In addition to a clinical exam, medical imaging is used to help determine whether a suspected tear is present. But accurately confirming the diagnosis, and correctly evaluating the severity of the injury, are both pertinent to deciding the best treatment path. While not all injuries will require surgery, when left untreated or improperly diagnosed, the condition may worsen with time.

To learn more about how to ensure an accurate diagnosis, we spoke with two Musculoskeletal Radiologists, Dr. Andrew Kompel and Dr. Nicholas Lewis. Here, they explain the different types of rotator cuff injuries, strengths of rotator cuff tear MRI evaluation, and more.

DocPanel is committed to providing radiology second opinions as specialized as the human body. Upload your scans, connect with the best-suite subspecialist, and have your questions answered by a leading radiologist in the US. Learn more here.

[DocPanel] Why is MRI considered the best test to diagnose a rotator cuff tear?

[Dr. Kompel]

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that surround the shoulder and assist with keeping the upper arm bone (humerus) in place with arm movement. The rotator cuff tendons, the portion of the muscle that connects to the bone, are prone to tear, especially as we age, and with repetitive motion because of their propensity to be impinged by the surrounding bones.

MRI is the best imaging test to evaluate the rotator cuff tendons because of the soft tissue contrast. This means that the tendons can be easily identified from the surrounding muscles and bones. A tendon tear will alter the normal MRI appearance, leading to the diagnosis.

X-Ray and CT scans have much lower contrast so the tendons blend with the surrounding tissues. Visualizing and diagnosing a tear on these studies can be difficult, or even impossible. Ultrasound does have the ability to identify rotator cuff tendon tears but with certain limitations. One factor is that it requires special training for the staff, as this is a less commonly performed imaging test. Second, the tendons may not be adequately seen in obese patients or those with a limited range of motion.

[DocPanel] Should a rotator cuff tear MRI be performed with or without contrast?

[Dr. Kompel]

In general, MRIs can be performed with or without contrast. If performed with contrast, that could include either IV contrast or intra-articular contrast. When a rotator cuff tear is suspected, the MRI is almost always performed without contrast. There is never a need for IV contrast when evaluating for a rotator cuff tear.

If you have had prior surgical rotator cuff repair, then your orthopedic surgeon may request intra-articular contrast. Intra-articular contrast requires an injection immediately before the MRI which is typically performed under fluoroscopy (a type of X-Ray) or ultrasound to place the contrast within the shoulder joint space.

[DocPanel] Will rotator cuff tears show up on an X-Ray?

[Dr. Kompel]

X-Ray is a quick and easy way to take an initial look at the shoulder joint. However, a rotator cuff tear will not be identifiable on the X-Ray. The bones and arthritis show up well on the X-Ray while the soft tissues, which include the tendons, are not able to be separated meaning tears cannot be identified.

One exception could be if you have a large, chronic rotator cuff tear. In that case, the bones may have mild alterations in their alignment which can suggest the presence of the tear. Though, even in this example, your doctor may still recommend an MRI for confirmation.

[DocPanel] What are the differences between a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, partial-thickness rotator cuff tear, and rotator cuff tendon impingement?

[Dr. Lewis]

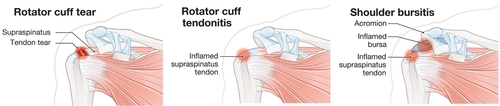

Rotator cuff tendon disease (tendinopathy or tendinosis) can be broken down into two categories: injuries and degenerative changes. Degenerative changes are to blame for the majority of painful tendons and can occur due to normal aging as well as overuse. This can happen at any age but starts to become more common after age 40.

Tendon degeneration might be accelerated if there are bone spurs rubbing against the tendon, causing it to fray and weaken over time. This rubbing against the tendon is called rotator cuff impingement. Impingement can be diagnosed without an imaging test, by the physical exam of an experienced doctor, but can also be directly diagnosed on live ultrasound while moving your arm.

Certain hobbies and occupations can exacerbate this impingement and associated tendon damage. The resulting tendon fraying requires an MRI or ultrasound to be seen, and is sometimes described as a "partial-thickness tear." The terminology can be confusing since some patients (and their doctors) assume that the word "tear" means there had to be an injury, and that surgery is required to fix the tear (not always true).

Of course, injuries to the rotator cuff also happen and can lead to tears. Often the two categories of tendon disease happen together. For example, if you injure your rotator cuff from a fall, it is more likely to result in a "full-thickness" tear if pre-existing degenerative changes were weakening the tendon.

[DocPanel] What are the associated risks with delayed or misdiagnosis?

[Dr. Lewis]

Getting the correct diagnosis on any imaging test ensures that you get the right treatment, and rotator cuff tears are no exception. In general, some partial-thickness rotator cuff tears do not require surgery and can be managed with physical therapy in the same way that rotator cuff tendinopathy (degeneration without a tear) is managed. Full-thickness tears, and partial-thickness that involve a majority of the tendon, usually will require surgery to restore function and reduce pain.

If the tendon is detached from the bone as in a full-thickness tear, the associated rotator cuff muscle begins to weaken and become replaced by fat over a matter of several months. This is called "fatty atrophy" and is an irreversible process. Even if surgery were done to repair the tendon, the muscle would remain weak and nonfunctional if atrophy has advanced too much. So getting the right diagnosis can be time-sensitive to ensure the best possible outcome.

[DocPanel] How do you know if your rotator cuff injury requires surgery?

[Dr. Lewis]

MRI and ultrasound are both good at diagnosing the type of tears which require surgery. However, MRI is the only reliable method to determine how much (if any) muscle atrophy has occurred, and therefore whether a patient would benefit from surgical repair of the tendon. If the tendon is not repairable for any reason, there are alternative surgeries that can be performed to restore shoulder motion and improve pain, such as reconstructing the superior joint capsule or replacing the shoulder joint with a "reverse" total shoulder arthroplasty. The latter is a more common procedure, especially if there is coexisting shoulder joint arthritis, and is called "reverse" because it switches the ball-and-socket arrangement of the normal joint to be opposite. This reversal of the ball and socket anatomy allows for greater shoulder stability without a functioning rotator cuff. So having your shoulder MRI correctly interpreted is essential to selecting the right treatment for you, whether nonsurgical or surgical.

[DocPanel] What can patients do to help ensure their rotator cuff tear MRI is accurately interpreted?

[Dr. Lewis]

While both MRI and ultrasound can reliably diagnose rotator cuff tears, no test is perfect, so there are some cases of "false negatives" (reported normal when actually there is a missed tear), and even "false positives" (called a tear when the tendon is in fact not torn). Generally, these tests are cited as being over 90% accurate. However, that figure is certainly much higher if your test is being read by an experienced radiologist with fellowship training in musculoskeletal imaging.

About the Contributing Radiologists:

Andrew Kompel, MD is a Musculoskeletal Imaging Radiologist and an Assistant Professor of Radiology at Boston University School of Medicine. Dr. Kompel completed his Diagnostic Radiology Residency at Boston University Medical Center followed by a fellowship in Musculoskeletal Imaging and Intervention at Johns Hopkins Hospital. His areas of clinical and research interests include collaboration with orthopedists in quantitative cartilage analysis, sports-related injuries, and advanced MRI imaging. He has co-authored multiple peer-reviewed papers, authored book chapters and review articles on musculoskeletal topics, and has given invited lectures and instructed at national Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Courses.

Nicholas Lewis, MD is an academic Musculoskeletal Imaging Radiologist and Assistant Professor at Wayne State University, School Of Medicine. Dr. Lewis completed his Diagnostic Radiology Residency at Wayne State University, School Of Medicine followed by a fellowship in Musculoskeletal Imaging at the University of Southern California. Dr. Lewis is a former consultant radiologist for the Detroit Tigers and Red Wings teams. His clinical interests include sports medicine, musculoskeletal intervention, ultrasound, as well as diagnosis and treatment of rare bone tumors.

Interested in getting a second opinion from Dr. Kompel, Dr. Lewis, or one of our other subspecialists? Learn more here.